ANTI-CUTE / CONTINUOUS REWARD

Title:

Continuous Reward

Date:

2018

Medium:

Solo Exhibition and Website Design

Role:

Art director, Producer, Illustrator, Animator

Description:

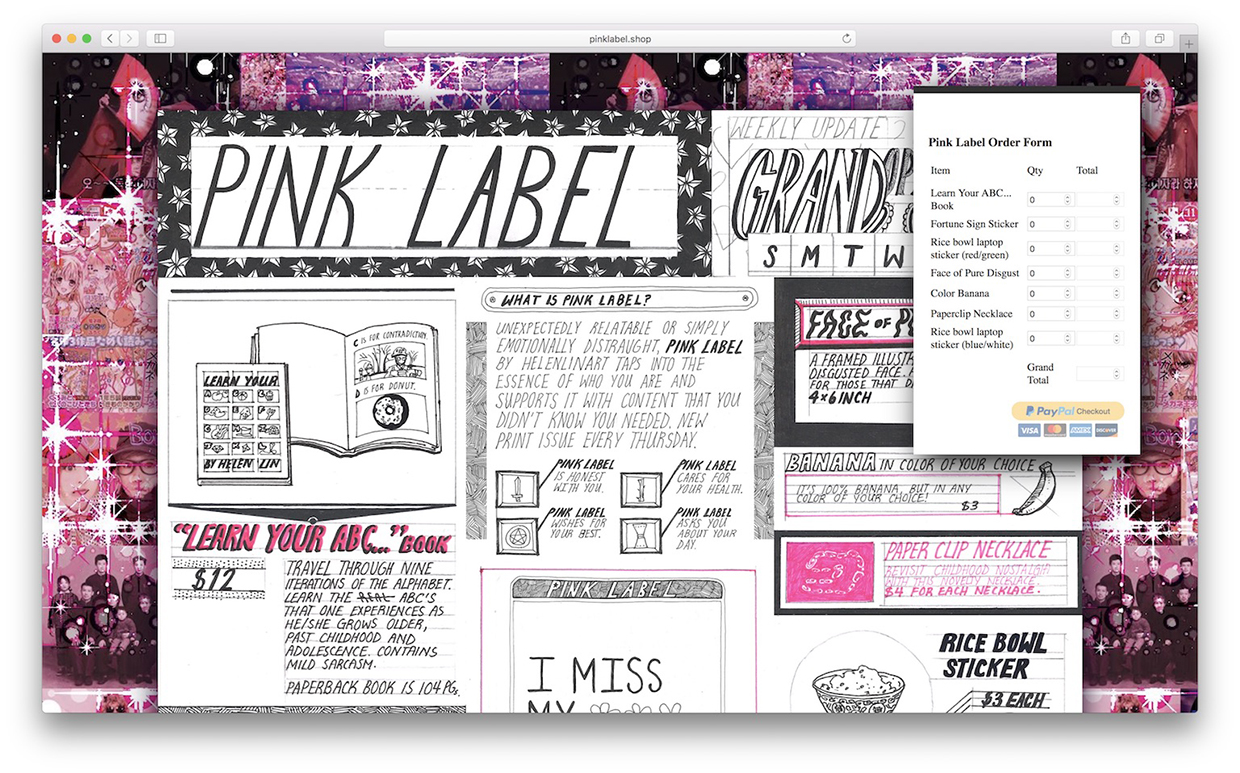

Pink Label Online Shop is a website project formatted like a newspaper circular. The concept was inspired by Coffee News, a weekly Canadian advertising publication that was formatted into three columns, with advertising on the left and right columns and information in the center column. My collaborator Eric Li Design) and I wanted to ensure that Pink Label’s distinctive hand-drawn style was legible on screen but also allow for intuitive functionality in viewing and purchasing the items. Shopsin’s General Store served as another inspiration for our barebones ordering form.

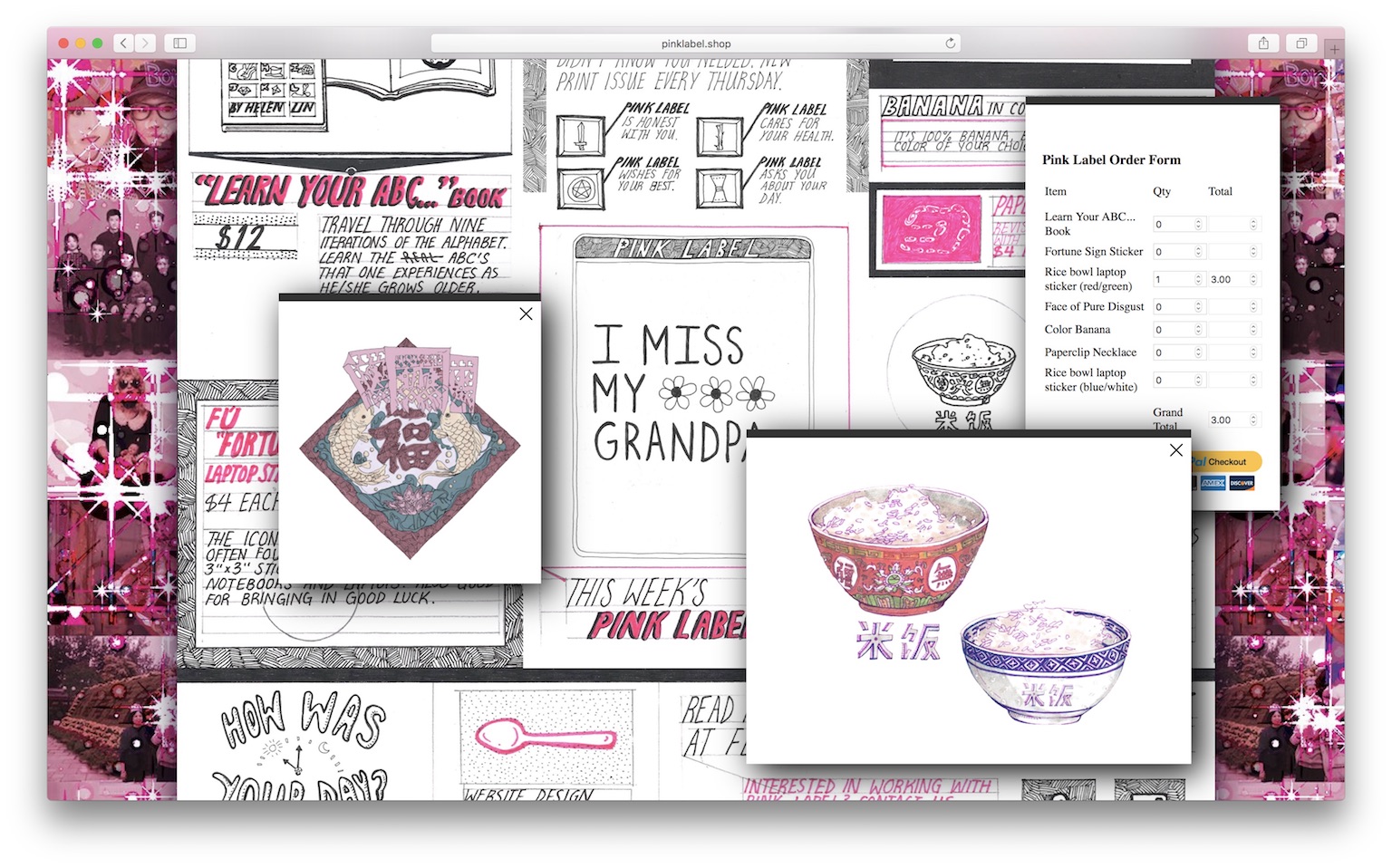

When users clicked on the product

advertisements, a small window within the browser pops up, showing what the product looks like in real life. The order form is fully functional and connects to PayPal when submitted; the buyer can expect to receive their product(s) within 1-2 weeks.

This website project was part of a year-long serialization zine project that published a new issue every Thursday and culminated into a solo exhibition at the end of the year. Each booklet displays just one piece of content pertaining to everyday life, and the topic could be focused around the cultural objects that we consume, clothes that we wear, and/or childhood memories that we hold. Each booklet links back to the shop where they can purchase products inspired by those same cultural artifacts as well. Content usually revolves around fashion, female adolescence, consuming East Asian pop culture or cultural products. Occasionally, content will be submitted by other writers, but they will all be written and illustrated by hand under the Pink Label aesthetic.

In 2018, I built the set and artwork pieces for my solo exhibition “Continuous Reward”, Lucas Gallery 185 Nassau Street, which presented the evolution of the brand experiment “Pink Label” and explored the Asian-American immigrant experience through “attainable” art (mass-producible items such as stickers, zines, accessories, books) that people can easily own. For several months leading up to the solo exhibition, Pink Label was exhibited in the Frist Campus Center display case with takeaway weekly zines--part of a year-long serialization with a new issue every Thursday. Each booklet displays just one piece of content pertaining to everyday life, and the topic could be focused around the cultural objects that we consume, clothes that we wear, and/or childhood memories that we hold. Content usually revolves around fashion, female adolescence, consuming East Asian pop culture or cultural products. Occasionally, content will be submitted by other writers, but they will all be written and illustrated by hand under the Pink Label aesthetic.

The zine pages are printed on two 8.5x11 inch paper front and back, folded, and cut to create a small sixteen-page booklet that easily fits in your hand. With this accessible publishing method, the zines can cheaply be reproduced using a standard copy machine.

“While cuteness can evoke ‘warm and fuzzy feelings’, it can also provoke ‘ugly or aggressive feelings’. She (Sianne Ngai) writes, ‘cuteness is not just an aestheticization but an eroticization of powerlessness, evoking tenderness for “small things”, but also, sometimes, a desire to belittle or diminish them further’. She explains that ‘in its exaggerated passivity and vulnerability, the cute object is as often intended to excite a consumer’s sadistic desires for mastery and control as much as his or her desire to cuddle’. In other words, the feelings of empathy experienced by the subject can easily become transformed into the opposite: violence and aggression towards the cute object. It is not surprising, then, that cute objects are often portrayed when they are in states of injury, weakness or shame: ‘Winnie the Pooh with his snout stuck in the beehive, or Love-a-Lot Bear in The Care Bears Movie, who stares disconsolately out at us with a bucket of paint overturned on his head’. In their states of humiliation, these helplessly cute characters invoke a relation of dependence by calling attention to their own state of powerlessness and need for ‘adult care’. This emphasis on powerlessness and dependency (mother–child) speaks to cute-ness’s grounding in a ‘peculiarly “feminine” proprietary desire ... the desire to care for, cherish, and protect’. Indeed, cuteness is not only invoked as a feminine aesthetic, but is historically and aesthetically entangled with childhood.” (Plourde, Lorraine. Babymetal and the Ambivalence of Cuteness)